There are the three acts to the drama that plays out when a police department gets exposed for excessive abuse of powers:

Act One: Major law enforcement official gets fired/ousted;

Act Two: Task force is created to study police practices and make recommendations for improvement;

Act Three: Police department selects a couple of recommendations it can live with (Chief Diversity Officer! Yes!) and goes back to business.

The main determinant of what a police department can or cannot live with is its police union—the usual foil to any police reform plan. The union often compels government forces to run any major proposed changes to policies or practices through union leaders, even if those changes are court-ordered. In Chicago, after a court ordered the city to turn over years of police misconduct complaints for public access, the local police union intervened by declaring that publicizing certain records would violate its collective bargaining agreement.

The NFL can’t even pass a ban on carrying concealed weapons without the police union busting the league’s balls for it. Police are supposed to protect and serve the public, but they’re overlorded by police unions that are there solely to protect and serve the police.

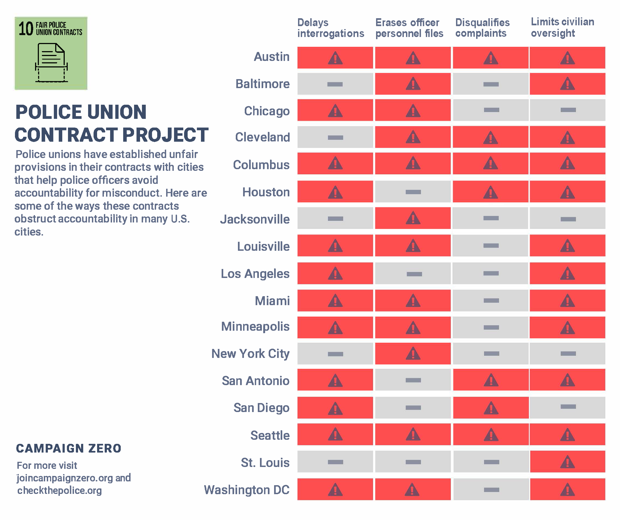

Which is why Black Lives Matter-affiliated activists have created a new campaign that illuminates some of the more troublesome provisions in police union collective bargaining. Campaign Zero’s Police Union Contract Projectscores the bargaining agreements that exist among various city police departments. There are four major criteria the activists use to evaluate how the contracts hinder police accountability measures. Of the 17 cities they currently have examined, Austin; Columbus, Ohio; and Seattle are red-flagged on all four measures, as seen below.

One of the criteria Campaign Zero measures is whether police union contracts command the erasure of police personnel files, which is a major problem in Chicago right now, as mentioned above. Police unions there are arguing that a collective bargaining agreement provides an exemption to Freedom of Information Act requests for personnel records that are more than four years old.

A trial court did grant the unions an injunction against handing over the older files to the public. Journalists have been in court fighting to free those records so they can report on police officers who have histories of civilian abuse but have evaded punishment for them.

This is far from the only case in Chicago where the police or the city have tried to keep misconduct files from the public. In the 2001 Doe vs. Marsalis case, regarding a Chicago police officer charged with sexually assaulting a woman, federal court judges vetoed the city’s attempt to shield documents associated with the case from the media. Said U.S. District Court Judge Ruben Castillo in his ruling:

Simply put, the average Chicago citizen is tired of being the victim—either direct or indirect—of repeated police misconduct. Police misconduct creates one of the ultimate “lose/lose” situations in our democratic society. … Ironically, the average citizen not only suffers these unquantifiable losses, but also is asked to foot the bill when local communities are forced to pay for the misdeeds of its law enforcement officers. In fact, the City of Chicago, a defendant in this case, just recently agreed to pay $18 million in the settlement of an egregious police misconduct case. … This ugly and expensive syndrome must come to an end.

It did not end. In 2009, in the Bond v. Utreras decision, U.S. District Judge Joan Humphrey Lefkow ruled against the police department’s wishes to, again, cloak police misconduct files under a protective order. Said Lefkow in her ruling:

The public has a significant interest in monitoring the conduct of its police officers and a right to know how allegations of misconduct are being investigated and handled. Without such information, the public would be unable to supervise the individuals and institutions it has entrusted with the extraordinary authority to arrest and detain persons against their will. With so much at stake, [police] simply cannot be permitted to operate in secrecy.

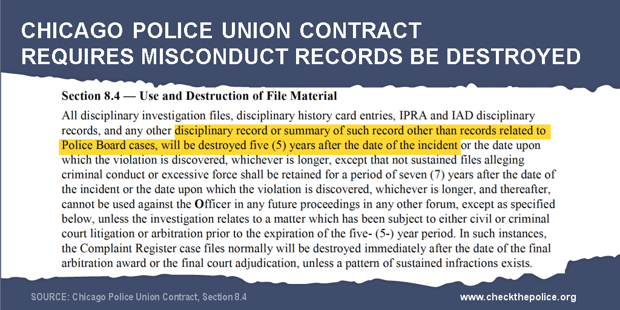

There are plenty more cases where those came from. Which is why, perhaps, it’s no surprise that the Chicago police union has consistently leaned on astipulation in its contract to destroy records older than five years. Media advocates have been arguing in court that collective bargaining agreement terms should comply with existing sunshine laws, not trump them.

As the Invisible Institute founder Jamie Kalven writes in a court brief seeking to block the police union’s prerogative to destroy older police files: “Any collective bargaining agreement provision that contracted away FOIA obligations and restricted the public’s FOIA rights would be invalid as violating the public policy necessary for a well-functioning democracy.”

Yet, as Campaign Zero’s Police Union Project shows, Chicago is not the only city where the police union seeks to delete police officers’ histories of misconduct. In Baltimore, the police department expunges any allegations of misconduct from a cop’s file if the complaint is dismissed for any reason. In Cleveland, verbal warnings and written reprimands are removed from cops’ files after six months, while more serious disciplinary actions get removed after two years. In Minneapolis, where a police officer killed an unarmed African American named Jamar Clark last month, investigations that don’t lead to a cop being disciplined are not entered into their personnel file at all.

It should be noted that just because a citizen complaint against a police officer isn’t sustained or doesn’t lead to some form of punishment, that doesn’t mean no police misconduct happened. In Minneapolis, people who have filed police complaints often haven’t heard back about whether an investigation was conducted, let alone about the outcome, and as state policy.

Other civilian complaints may get dropped because a person fails to show up for a hearing or won’t comply with a follow-up investigation. It’s understandable why this happens: People fear retaliation from cops for going up against the Blue Wall. That wall is often fortified with police union contracts designed to erase police officers’ histories—perhaps in fear that civilians might one day legally retaliate for repeated harassment and abuse.