New Orleans police barged into the Allen family home on March 7, 2012, armed with a search warrant secured only minutes before and with a lot of guns. One of the cops was also armed with a stealth video-recording device, unbeknownst to his squad. Within seconds of tearing through the house’s back door and first floor, which was filled with children, Officer Joshua Colclough ran up the steps and encountered Wendell Allen, who the officer then shot in the chest.

Allen, 20 years old, was unarmed and was wearing only pajama bottoms. He died from Colclough’s shot. Allen’s brother and a friend, both 19, witnessed the shooting. Normally it would have been their word against the police’s in terms of who was at fault. At least one police investigator was reportedly framing the crime scene interrogations in terms that suggested Allen was trying to killColclough.

Two things stopped that story from becoming the prevailing narrative: the secretly recorded video of the sting, and the independent police monitor whoreviewed the investigation. Ultimately, Colclough pled guilty to manslaughter and is serving a four-year sentence in jail. The Allen family has filed a federal civil suit against the New Orleans Police Department, which has not yet been resolved. It’s clear from the many investigation reports released about this incident that Allen’s family would not have achieved justice without the video and the police monitor.

This sounds like a compelling example of police accountability in action. But in fact, it may result in getting New Orleans’ independent police monitor fired.The New Orleans Advocate newspaper reported on Friday that the city’s Inspector General, Ed Quatrevaux, wants the Chief Independent Police Monitor Susan Hutson gone. According to The Advocate, the reasons for this stem from years of squabbling between the two city offices, including the inspector general’s disgruntlement with the police monitor for releasing information about violent police to the public without his permission.

If the inspector general gets his way, this may prove to be an example of what happens when civilian police oversight becomes too effective—or at least, too independent. Meanwhile, legislators in a number of places have tried to pass legislation that would limit or prevent public access to video evidence of police violence.

This raises a few questions: If a police officer shoots or harms someone on camera but the public can’t see the video, did it happen? In cases where video is released, how does the public know that it hasn’t been tampered withwithout someone independent from the police monitoring the investigation? To paraphrase Boogie Down Productions’ 1989 question: The police are sent to protect, but who ensures protection from the police?

Government-created commissions and social-justice organizations are both trying to pin down answers to these questions. The Forward Through Ferguson Commission, created in the aftermath of the police killing of Michael Brown, made a broad call for civilian oversight of police in a 198-page report released earlier this month. Civilian police review boards, independent police monitors, and similar oversight entities have been around for decades, working somewhat impressively in cities like Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. In Atlanta, the police chief swaps phone numbers with organizers ahead of demonstrations to keep an open line of communication during protests and rallies.

David Harris, a policing expert at the University of Pittsburgh, tells CityLab that the effectiveness of civilian oversight—whether through review boards or monitors—boils down to a few things:

“Is it independent? Does it have its own governing board, and its own subpoena power? Does it have its own non-law-enforcement investigators, its own budget and a working staff? That’s the minimum package required for these things to succeed,” says Harris. “In a lot of cities, in how they’re set up, they don’t have all those things.”

Without those ingredients, efforts to produce effective civilian oversight can actually end up becoming counterproductive, which Harris says he’s seen happen.

Sometimes how it goes is, “police oversight reforms get proposed and put in place by a city, but they have not given [the reforms] the proper tools to succeed, and after a short time people think it’s a paper tiger,” says Harris. “When you have what sounds like what should be an impressive way of ensuring policing accountability, but they see it goes nowhere, a lot of times these things have not only not helped inspire community confidence in the police, they actually hurt it.”

Communities of color are lately demanding more muscular regulation of police operations that includes the full suite of features Harris describes—the “non-law-enforcement investigators” in particular for instances when police kill.Campaign Zero, a policy platform generated by Black Lives Matter-associated activists, has made this an essential component of its police-reform agenda.

In Wisconsin Professional Police Association Executive Director James Palmer’s testimony to the White House’s 21st Century Policing Task Force, he said that any police-involved-killing investigation should be “conducted by at least two investigators … neither of whom is employed by a law-enforcement agency that employs a law-enforcement officer involved in the officer-involved death.”

New Orleans is one of the few cities that has a monitor who’s not on the police force, but who has powers to audit investigations into civilian injuries and deaths caused by police or those that occur while in police custody. The independent police monitor’s office was approved by 70 percent of New Orleans voters in 2008 through a ballot referendum, and was activated in 2009 under the city’s Office of Inspector General. It’s led by a civilian, Susan Hutson, an attorney who worked for Los Angeles’ inspector general’s office prior to coming to New Orleans.

The city also has a federal monitor who ensures compliance with the consent decree between the New Orleans Police Department and the U.S. Department of Justice. The city’s independent monitor is part of that consent decree, meaning that any violation of the independent-monitoring requirements is considered a violation of the federal agreement. The federal monitoring team, which is composed mostly of past and present police chiefs from other cities, is also led by an attorney, Jonathan Aronie, who once served as deputy independent monitor for the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C.

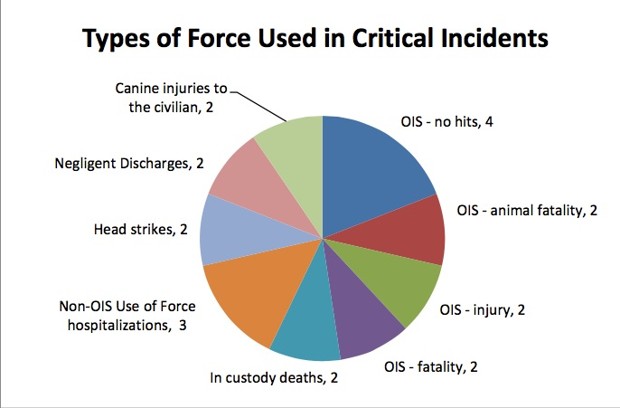

In New Orleans, there are additional layers of monitoring from the Public Integrity Bureau and the Force Investigative Team, which are both made up of city police. The bureau is essentially an internal affairs department, while the investigative team is a separate unit under the bureau that focuses specifically on officer-involved violence.

It’s a whirlwind of monitoring, but it’s warranted—as the consent decree, ahistory of corruption, and the well-circulated stories of police brutality during Katrina made abundantly clear. Yet, it also creates the kind of wire-crossing and barbed entanglements that currently have the independent police monitor’s job in jeopardy.

Last week, Inspector General Ed Quatrevaux sent a letter to the city’s Ethics Review Board asking to eliminate Hutson from her post as chief police monitor. Her office sits within the inspector general’s office, and the inspector general determines the monitor’s budget. But Hutson has accused the inspector general of creating a hostile work environment, and of compromising the independence of her monitoring team. It’s gotten so bad that both offices are, or at least were, working on amending the city’s charter so that they can officially divorce.

Quatrevaux cited a few reasons for wanting to get rid of Hutson—one of them being a scathing report the monitor recently released that categorically ripped apart the police department’s investigation into the 2012 killing of Wendell Allen. Quatrevaux believes all police reports need his approval before they’re released to the public. Hutson maintains that this would essentially undermine her office’s obligation to the public, which is to bring transparency to police actions, especially in matters of life and death.

This is the kind of scenario that could play out in other cities as they design new infrastructure for law enforcement oversight. Independent police monitoring is endorsed from Ferguson to the White House—on paper. But if independence is not clearly defined in the design, then problems like the one in New Orleans are fated to arise. Establishing independence in this context boils down to how transparent the police, and their unions, will allow themselves to be.

In the Wendell Allen case, transparency was forced. It was the independent police monitor’s office that coerced the police department into collecting the video evidence from the cop who recorded the sting operation—evidence that New Orleans police didn’t even want to acknowledge existed.

The police monitor then released the video recording of Allen’s killing to the public, against the police department’s wishes. It was the only way to refute the police’s narrative of what happened. The police initially claimed, and havemaintained, that they announced themselves before barging into Allen’s house. The video proved that they didn’t. The police also initially stated that Allen might have attempted to attack the police officer. The video proved this false as well.

This summer, the independent police monitor also released video of a New Orleans cop who beat a mentally ill 16-year-old girl. This rankled the inspector general and a court judge, who then reportedly directed the police department to limit the monitor’s access to video evidence.

When it comes to police violence: Pics, or it didn’t happen. This is why the independent police monitor has insisted on video evidence, but according to Quatrevaux’s letter, such evidence led the judge to accuse Hutson of “attempting to ‘sensationalize‘ police incidents.”

This alone illuminates the unbalanced scales of justice in law enforcement. Police can instantly publicize video of civilians committing crimes—thinkMichael Brown in Ferguson. It doesn’t matter how trivial the criminal violation. In fact, many believe that aggressive cracking down on even the mildest of crimes is good policy. But there’s no “broken windows” theory for cracking down on police misconduct, just broken transparency.

New Orleans’ Ethics Review Board will hold a hearing on October 23 to consider whether to honor the inspector general’s request to fire the police monitor. The board’s decision will signal to other cities designing their own police monitoring reforms just how much independence is considered too much.