The Supreme Court is expected to rule any day now on the case of Harris v Quinn, a somewhat obscure tale of a mother’s reimbursement payment for providing her disabled son with home-based health care that’s exploded into a potential political earthquake that potentially holds the fate of public sector labor unions in the balance.

Here’s what you need to know to get caught up to speed before the court acts.

What does the plaintiff want?

IT IS NOT IN THE INDIVIDUAL INTEREST OF ANY PARTICULAR WORKER TO BE PAYING UNION DUES

Nominally the case is about labor union representation of home health care workers in Illinois who work with disabled patients. The plaintiff, Pam Harris, is the mother of Josh Harris who has Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome, a severe illness that leaves him in need of constant care. Illinois provides a modest financial benefit for people in need to hire home-based health care on a contract basis. Like many recipients of disability benefits in Illinois, Harris has contracted with a family member — in this case his mother, Pam — to be his caregiver.

Pam Harris isn’t a member of a unit that’s represented by a labor union, but many Illinois home health care aides are represented by either the SEIU or AFSCME. If you are in a unit that votes for union representation, then you have to pay a representation fee to the union (unions call it a “fair share” fee). Harris is asking the Supreme Court to rule that it’s unconstitutional for Illinois to make workers whose units are represented by a union to pay the fee. And standing behind Harris is the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, backed by the usual array of conservative moneybags types, including the Bradleys, the Waltons, and Charles Koch.

What are the stakes?

Broadly speaking, the stakes are whether or not labor unions will continue to be viable in the United States public sector. Collective bargaining is, by definition, a collective action problem. To the extent that SEIU does useful work on behalf of Illinois home health care workers, all Illinois home health care workers benefit. No matter how beneficial the existence of a strong labor union may be for the workers who are members, it is not in the individual interest of any particular worker to be paying union dues.

That’s why successful labor unions typically fight for arrangements where all workers who benefit from the union’s activity must pay a representation fee. Absent such a mandatory fee, the tendency is for a union to unravel. Even when workers collectively prefer a strong union, it can’t stay if everyone is allowed to decide à la carte whether or not to pay. In so-called right to work states these kind of arrangements are illegal, and labor unions are generally very weak.

A THIRD OPTION IS TO SPLIT THE BABY AND HOLD THAT THE ABOOD PRECEDENT IS STILL GOOD LAW BUT DOES NOT APPLY IN THIS CASE

Harris’s legal argument could essentially turn all states into right to work states for the purposes of the public employees. And it could even set a precedent for a constitutional ruling extending the right to work principle into the private sector.

What’s Harris’ argument?

Harris and her supporters view her as being forced to financially support a political cause she does not endorse. They argue that since the employer a public sector union bargains with is a government, the “bargaining” that public sector unions undertake is really a form of political activism. Therefore representation fees represent a kind of mandatory political activism. Mandatory political activism violates the First Amendment.

By one of those happy coincidences that tend to arise in American constitutional law, the groups backing Harris’ legal argument also think strong labor unions are bad economic policy while her opponents think the reverse.

What options does the Court have?

One option, preferred by liberals, would be to simply reaffirm the precedent set in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education holding that public sector collective bargaining is fine, and public sector unions can have agency fees.

Another option, preferred by conservative activists, would be to overturn Abood and immediately institute a nationwide right-to-work policy for public sector unions.

A third option is to split the baby and hold that the Abood precedent is still good law but does not apply in this case. The argument here would be that Illinois health care workers are not really collective bargaining at all. They are individual contractors employed by specific individuals merely receiving reimbursement rates set by state law. That means that SEIU efforts to raise reimbursement rates are political activism that’s different from the kind of collective bargaining engaged in by the Detroit public school teachers in the Abood case. This would set the stage for lots of future litigation around different public sector arrangements as to whether they should be covered by Harris or Abood precedents.

A fourth option would be to just go hog-wild and find that any kind of legally sanction mandatory union representation fee is a violation of first amendment rights to free association. This would kneecap private sector unions as well.

How big a deal would a pro-Harris ruling be?

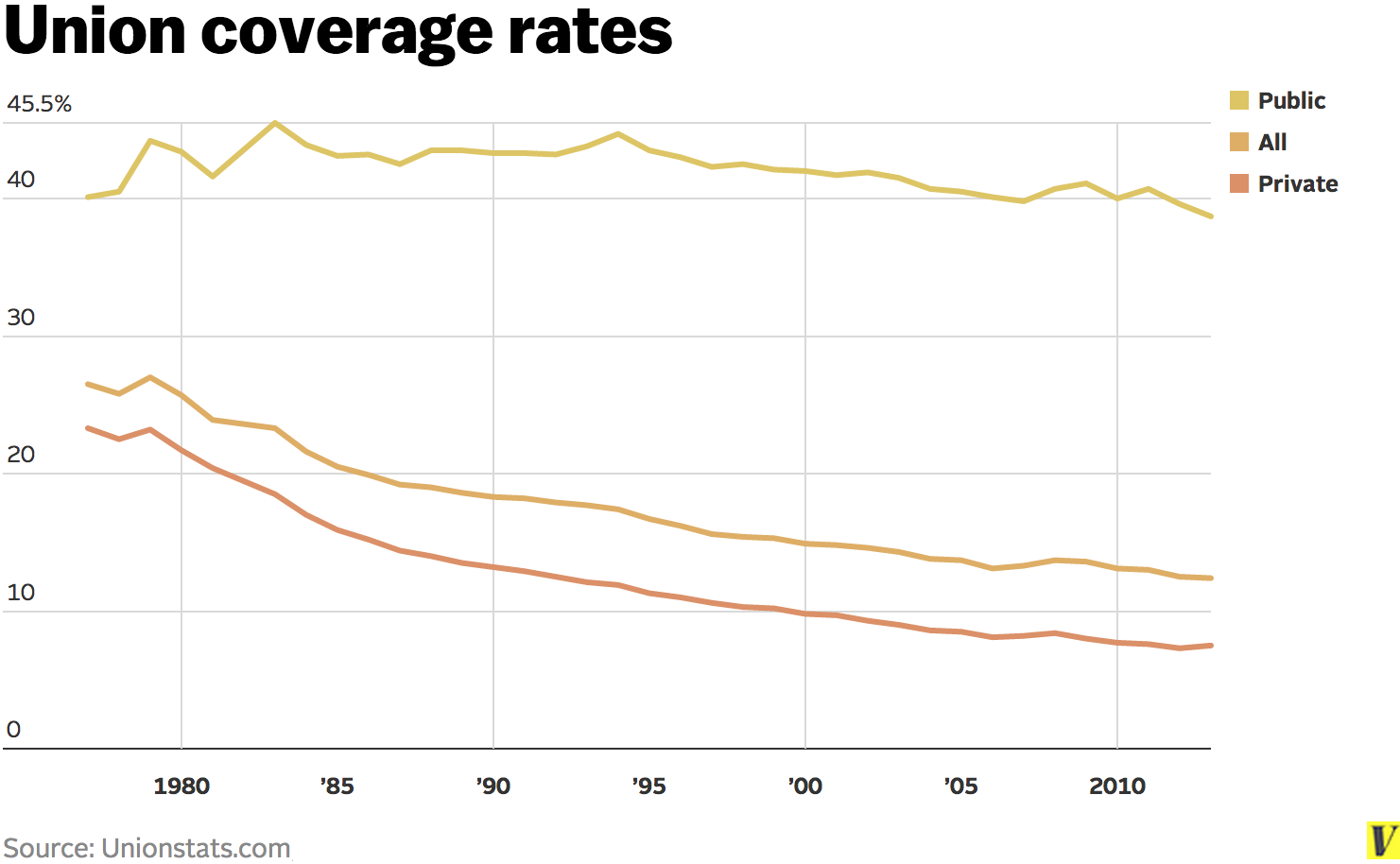

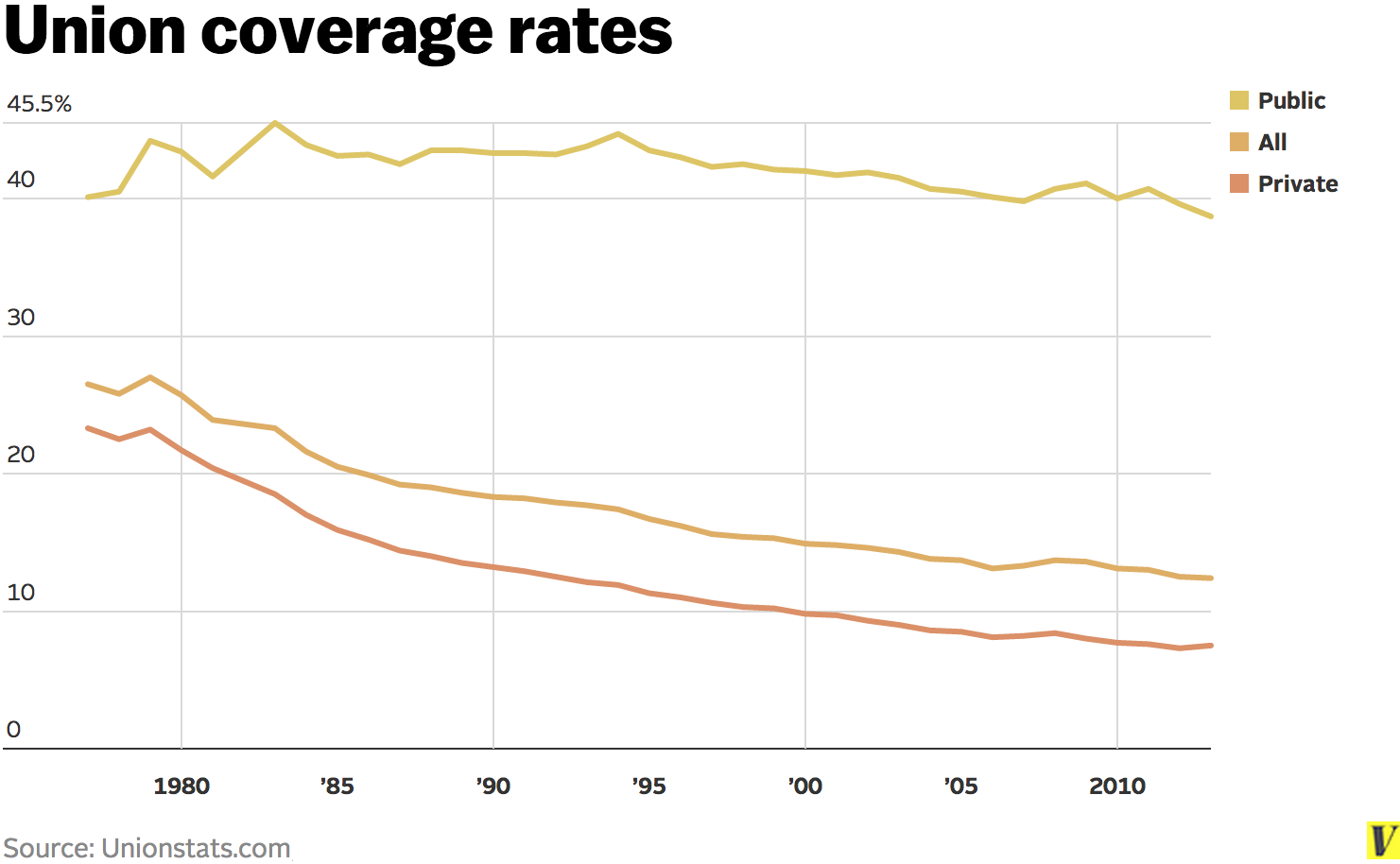

On one level, it would be a huge deal. Unionization rates in the United States are much higher in the public sector than in the private sector, and the biggest and most influential labor unions in the country tend to either represent public workers almost exclusively (AFSCME or AFT) or else, like SEIU, represent many public workers alongside private ones. Even quintessentially private sector unions such as the United Auto Workers are finding many of their growth opportunities in representing public sector workers such as state university graduate teaching assistants.

On another level, even a Harris loss would not exactly alter the bleak big picture landscape for the American labor movement. Republican Party politicians in traditionally union-friendly states such as Wisconsinand Michigan have demonstrated an eagerness to roll back union-friendly rules whenever they get a chance, whereas Democratic Party politicians in right-to-work states like Virginia hesitate to press for changes. Obviously a loss in the Harris case would greatly accelerate the prevailing trend, but it’s already the prevailing trend.

On another level, even a Harris loss would not exactly alter the bleak big picture landscape for the American labor movement. Republican Party politicians in traditionally union-friendly states such as Wisconsinand Michigan have demonstrated an eagerness to roll back union-friendly rules whenever they get a chance, whereas Democratic Party politicians in right-to-work states like Virginia hesitate to press for changes. Obviously a loss in the Harris case would greatly accelerate the prevailing trend, but it’s already the prevailing trend.

Is public sector collective bargaining good or bad?

Needless to say, people disagree! Here’s Josh Barro, then of the Manhattan Institute, making the case for tough anti-union measures in state government. Here’s Nelson Lichtenstein making the case that the overall success of progressive politics depends on strong unions, including in the public sector.

A more nuanced argument comes from sociologist Jake Rosenfeld, author of the recent book What Unions No Longer Do. Rosenfeld’s book is broadly pro-union, finding that the decline of labor unions is a major driver of rising inequality and wage stagnation among other ills. Rosenfeld argues that public sector unions don’t really work to curb these trends, because public sector workers tend to be better-educated and higher-paid than the average American regardless of union status.

But of course unions play other roles besides their direct one in altering the wage structure — notably they intervene in politics, typically on behalf of progressive causes. That political role of unions is key to the logic of Harris’ legal argument and it’s also where the impact may be felt the strongest if she prevails.

Correction June 3: This article has been updated to more accurately reflect Harris’ current union status.

http://www.vox.com/2014/6/3/5775516/the-supreme-court-could-cut-union-membership-in-half