Three years ago, then-Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and the City Council voted to reduce the retirement benefits they would offer to future civilian hires, in an effort to curtail the growing pension costs that have been consuming more and more of the city budget. This year, those costs ate up 20% of the general fund, leaving less money to spend on police patrols, street paving, park cleaning and other city services. The 2012 vote for pension reform was expected to save $6.9 billion over 30 years, and it was widely hailed as the foundation needed to put L.A. on a path for financial stability.

The result is that on Tuesday, the Los Angeles City Council is expected to vote on a new four-year labor contract that also rolls back the aggressive pension reforms.

Under the new plan, the retirement age for future employees would be 63, not 60 as it has been for most of the city’s history, or 65 as the 2012 plan would have required. The new plan would cap pensions for new hires at 80% of a retiree’s salary, which is more lucrative for retirees than 75% approved three years ago, but less generous than the previous retirement benefit that allowed veteran employees to retire with 100% of their final salary. Also, under the new plan, future employees would not have to contribute additional money toward their own pensions in years when the pension fund doesn’t generate sufficient earnings. The previous plan had included a cost-sharing requirement.

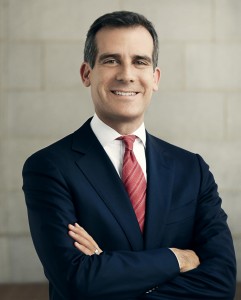

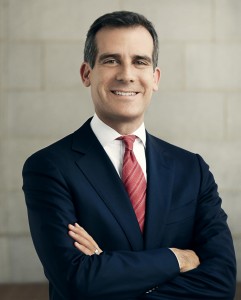

Mayor Eric Garcetti, who voted for the 2012 reform when he was a councilman, and City Administrative Officer Miguel Santana say the rollback was necessary. The risk of losing in court and having to negotiate a new pension plan from scratch was too great. That may be true. The new pension plan would save $5.2 billion over 30 years, but Garcetti and Santana argue that they were able to get additional savings — as much as $16.8 billion in total — by combining modest pension reform with no cost-of-living pay hikes for three years, lower starting pay and less generous “step” pay increases. (The deal includes a 2% raise in the fourth year.)

The fact remains that Los Angeles did not solve its pension and compensation problems with the 2012 reform, and the new proposal will still leave the city with an enormous financial burden. L.A. is paying down a nearly $9-billion unfunded liability for the city’s civilian and fire and police pension systems. And there is increasing concern that the city’s pension fund, like others around the country, relies on overly optimistic assumptions about how much its investments will earn, and that taxpayers will, again, have to make up the difference when the projections fall short. Los Angeles’ pension systems have an expected rate of return of 7.5%. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System recently voted to change its projected rate of return to 6.5%, which some observers still consider to be too optimistic.

Garcetti pledged to hold the line on raises for two to three years and require that employees pay 10% toward the cost of their healthcare in an attempt to cut costs immediately and end the city’s long-standing structural deficit by 2018. But the healthcare contribution was dropped during negotiations. The costs associated with the coalition contract and the change in the pension plan may prevent the city from closing the deficit by another year. Garcetti and the City Council are not done with pension reform or difficult budget choices.

http://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-la-city-pensions-20151208-story.html