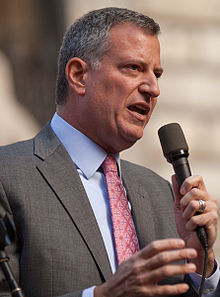

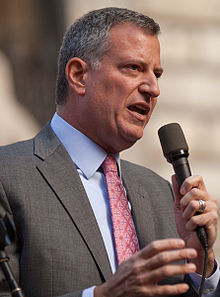

In the face of mounting criticism of his record on transparency, Mayor Bill de Blasio called for changing a state law that the city has said blocks the release of details about disciplinary actions taken against New York City police officers.

The mayor, in a written statement issued on Friday afternoon, said the statute, a section of the state’s civil rights law, was flawed and that the “public interest was disserved” by it.

The section, 50-a, has been at the center of a legal dispute over disclosing the disciplinary history of the officer who placed Eric Garner in a fatal chokehold. The law has been a longstanding obstacle to civil rights groups, reporters and others seeking information about misconduct by police officers and corrections officers.

“Without significant changes to this statute, the city remains barred from providing New Yorkers with the transparency we deserve,” the mayor said. “We hope advocates for greater transparency will join us in the effort to reform this state law.”

But critics of section 50-a said the problem is not only with the statute itself, but with the city’s expansive interpretation of its protections, driven by a deference to the unions representing uniformed workers.

On Friday, the proposal was met with criticism not just from the largest union representing police officers but also from police reform advocates and civil liberties groups that have been pushing for disciplinary information to be released.

In a statement, Communities United for Police Reform dismissed the mayor’s proposal as “not substantive reform or a genuine commitment to full transparency.” Others noted the challenging odds of the legislation being enacted.

“It is nothing more than a way to avoid responsibility for the mess the administration itself created,” said Christopher Dunn, the associate legal director at the New York Civil Liberties Union, which was fighting to make public some of the same files City Hall said it wanted to unveil through a legislative change.

“We’ll all be dead and buried,” Mr. Dunn said, “before the New York State Legislature turns its back on the police unions and rewrites the law to make public more disciplinary materials.”

Mr. de Blasio, a Democrat whose 2013 mayoral campaign championed police reform, has disappointed some who supported his run, creating a potential liability in the 2017 election on an issue that has been a key part of his appeal to liberals, particularly among black voters.

Mr. de Blasio has appeared increasingly conscious of the vulnerability, and in recent weeks his administration has been highlighting his reform efforts.

The law he is seeking to alter, section 50-a, has been in place for four decades. It says that the records of police and corrections officers, as well as firefighters, that would be used to evaluate their performance or employment status are considered confidential and should not be available to outside review without the person’s written consent or a court order.

City officials have argued that the law prevents the release of summaries of misconduct by Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who held Mr. Garner in the chokehold in 2014, before his death. Earlier this year, the Police Department cited the law in changing a decades-old practice of making available to reporters basic details on disciplinary actions.

Under the mayor’s proposal, the confidentiality protections would be eliminated for disciplinary records of officers who are being prosecuted by the Civilian Complaint Review Board, making the records of proceedings and the results public. In such cases, the department would post an officer’s name, charges against him or her, transcripts and exhibits from department hearings, summaries of the trial judge and the commissioner’s determination.

“I believe in transparency,” James P. O’Neill, the city’s police commissioner, said in a statement. “I also believe that making information about disciplinary proceedings public will help us build trust with the community.”

The announcement of the proposal included statements of support from community leaders, civic groups, members of clergy and other elected officials. “This is a step of progress in the right direction,” said City Councilwoman Vanessa Gibson, a Democrat from the Bronx and chairwoman of the public safety committee.

But Patrick Lynch, the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, said the statute was essential to protect information about police officers.

“Removing these protections will put police officers at greater risk of the types of targeted attacks we have seen with increasing frequency,” Mr. Lynch said in a statement. “It may also allow criminals to evade justice by turning criminal trials into smear campaigns against hard-working police officers, using issues that have little to do with the guilt or innocence of the accused.”