In this, San Francisco has fared better than some. The city has not been forced to declare bankruptcy in order to restructure its pension payouts, a la Vallejo, Stockton, or San Bernardino (where, as of 2012, a city with more than half of its residents on general assistance was spending 72 percent of its budget on police and fire department salaries and benefits).

But the city did have to increase various fees to cover its bills during the recession. Parking tickets and other fines all went up. This, or something similar, may have to happen again in light of the news today that the city’s rising pension costs are causing a $99 million budget deficit. A chief reason is that the return on the city’s investments haven’t met expectations — which is something that anyone could have predicted. And, as it turns out, many of us did.

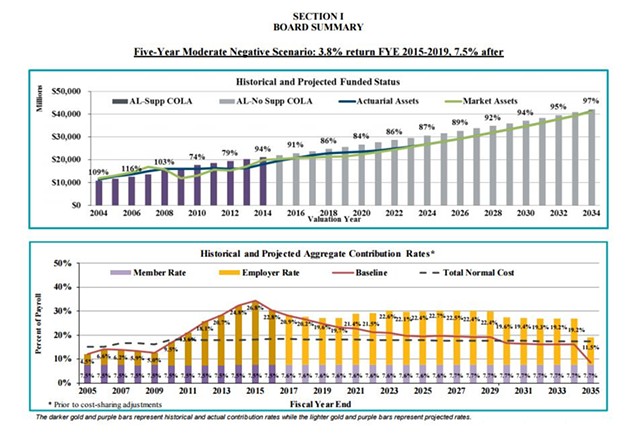

First, some basics. According to the most-recent actuarial reports available, the city has an unfunded pension liability of just short of $4 billion, on assets of about $19.2 billion.

That means that as of 2014, the city’s pension fund was 94 percent funded. (For comparison’s sake, as of 2007, the city’s fund was 125 percent funded — and in 2010, at the depths of the crisis, when the city was weighing pension reform options, it was 74 percent funded.)

As the Chronicle’s Matier and Ross reported today, slower than expected returns on the city’s investments have led to the projected shortfall, which in turn has led Mayor Ed Lee to ask city departments to cut their budgets by 1.5 to 3 percent. In this time of tech plenty, the city has been earning only about a 4 percent annual return on its investments, instead of a 7.5 percent annual return. “This is not what we expected,” City Controller Ben Rosenfield told the newspaper.

Except it’s what everyone else — that is, fiscal observers not running a public employee pension plan — expected.

According to Moody’s, an annual average return of 4 percent on pension funds is a reasonable expectation. That does not take into account the predictable fluctuations whenever our cyclical markets take their plunges. San Francisco’s expectation, then, is almost double what is reasonable.

That hasn’t stopped nearly every public employee fund in the country from tying its future projections to returns of between 6 and 8 percent.

So what happens if returns continue at a rate of about 4 percent or so? The unfunded liability grows — steadily.

As you can see, on 3.8 percent returns, the unfunded liability grows — again.

There’s no guaranteeing what will happen with the markets — if there was, we wouldn’t be in this job — but it seems safe to presume that pension troubles are here again.